It’s a truism in real estate that the 3 most important things in selling a property are location, location, location, because everything else can be fixed. (And real estate is admittedly on my mind right now; we’re trying to sell our townhouse. Don’t worry, this is an investment property, not our home; the sale isn’t indicative of any big changes going on in our cruising life).

Built into our character in the U.S., I think, is an underlying assumption that is so ingrained that we aren’t even aware of it. We believe that your life can be improved if you just move to the right location. Maybe it comes from being a nation of immigrants and second sons who crossed the ocean in search of adventure and opportunity. The belief applies whether the move is on a local scale, just across town to a new house in a new neighborhood, or a major move across the country. At its best, it gives us an attitude keeps us mobile, keeps us open to new ideas and new places, keeps us from getting complacent. There’s a down side to this as well, I’ll get to that in a bit.

In our home marina, we have a nice slip on the outer row with easy access to take the boat out and go sailing, and a pleasant view from the cockpit when we’re in the slip. But when you live on a boat, this whole moving-for-a-better-life thing is even more so, because the moving is so easy. No packing, no househunting, just up the anchor and go. Find the new better place, drop anchor. So it was with our boat slip. We have been extremely happy with our specific spot. Until, that is, our friends vacated their slip, just a few hundred feet away, same marina, same dock, better view, but more exposed. Would our lives get better if we moved over there? The ultimate local-scale move, about 150 feet further north. Would this improve our lives? I was all for giving it a try; Dan had all kinds of concern about whether the geometry of the new slip would allow us to tie up securely against wind and storms.

With the tolerant permission of the dockmaster/slip administrator for our marina, we arranged to spend a weekend at the new location to check it out. Friday afternoon we gathered some spare docklines and headed over. It was a 5-minute trip that ended in a graceless docking debacle, fortunately with no witnesses, but a short time later we were tied up. We were expecting some stronger winds on Sunday that would give us a real chance to test how well we’d resist the wind, so Dan spent what seemed like a couple of hours fine-tuning the docklines. When he was satisfied we headed to the cockpit to unwind with a beer and check out our new, if possibly temporary, view. It was indeed nicer than our old slip. The friends who had been here before had said that it was so peaceful and private that it felt like they were anchored out even when they were in the slip. The view out one direction was the anchorage; the other way was a carefully landscaped sloping hillside. In our old location, the window above the range gave a view of the side of the neighbor’s boat; here, it showed water and the boat traffic further downstream. “So, what do you think?” I asked. “It’s pr-r-r-etty nice,” Dan agreed.

We had an ordinary weekend planned, filled with minor errands, relaxation, some time with friends. But every few hours we interrupted ourselves, asking each other whether on the whole, this location was better or worse than our last one, cataloguing the plusses and minuses. For the big ones, view and exposure, we already knew what the tradeoffs were. But there were lots of little subtleties. Wifi speed? Plus one for the new slip. Finger pier on the starboard side of the boat instead of port? Plus one for the old slip. It should have been a perfectly nice weekend, except we had this decision hanging over our heads, a decision that grew in importance until it became monumental and drained the pleasure out of everyday things. Everything we did was examined and compared. The walk to the car? Shorter; plus one for the new slip. Stern access for the winter? A bit worse; plus one for the old slip. We were closer to the party pavilion: peoplewatching the guests? Plus one for the new slip. The guests walking the dock watching us? Plus one for the old slip. And we could better hear the music for the parties: that could be plus one for the new slip or the old one, depending on whether we liked the genre they were playing. We exulted in the new view and the light that reflected off the water and danced on the ceiling and cringed when the wind blew us toward the pilings or shifted a boat in the anchorage to come closer to our exposed side. We asked the friends that came to visit, and polled our Facebook page, for their opinions. View? Or security? We walked back to the old slip and stood there for a while, gazing out to the creek. Then walked back to the new one, and looked around. Then back to the old one. By Monday morning, we had to commit -- call and let the marina know, one way or the other, where we were going to stay for the rest of the season, and maybe longer.

What was weird, though, was that Dan and I had changed viewpoints. Now he was the one who was enchanted by the view, and I was the one who felt vulnerable and exposed. Now he wanted to stay and I wanted to go back. File it under “things that make you go ‘hmmmm.’”

There’s a theory that our decision-making style has an effect on our happiness. The theory says that there are two types of people, one who obsesses about making the best possible decision, the other wants to make a good-enough decision. Say you are trying to decide where to live. You could list your 3 or 4 most important priorities in a place to live, attributes like climate, recreational opportunities, job market, culture, cost of living, whatever matters to you, and the very first place that has those things, you make a good-enough decision and move there. Then you stop spending energy on deciding, and go on to build your life there, and don’t look back. No what-ifs. Or you could spend months looking for the very best possible combination of those things and many others, spending lots of time and energy to refine your choice, and even after you have made the choice, you always have this nagging concern, you are always second-guessing your call, that maybe if you had changed this one minor feature, your total happiness might be just a tiny bit more. But meanwhile, and maybe forever, you spent a lot of time worrying. The downside of being in a culture that believes that you can affect how good your life can be by choosing or changing your location, is that wherever you are, you are not content to simply enjoy it, you are always looking over your shoulder to see if there is an even better place you could be. As my friend RoseAnn puts it, you miss the good thing you have right in front of you because you’re so busy looking for the next, better, thing -- because if you find an even better place, you will have an even better life.

I began to fear that the great boat-moving experiment was going to be a bit like that obsessive second type of decisionmaking. We were going to be in the same marina, same dock; all we were doing was moving 150 feet. A lot of angst over a difference that really made little difference. Both places were okay! One had a little nicer view, the other was a little more protected. And it’s a boat! It moves; that’s the whole point! Four months from now, we’d be taking the boat south for the winter and it would be all moot. So why was this so hard? Maybe because the differences were so minor? As another friend, Margo, asked, “If this opportunity hadn’t come up, would you have been unhappy enough where you were to consider moving, or were you satisfied there?”

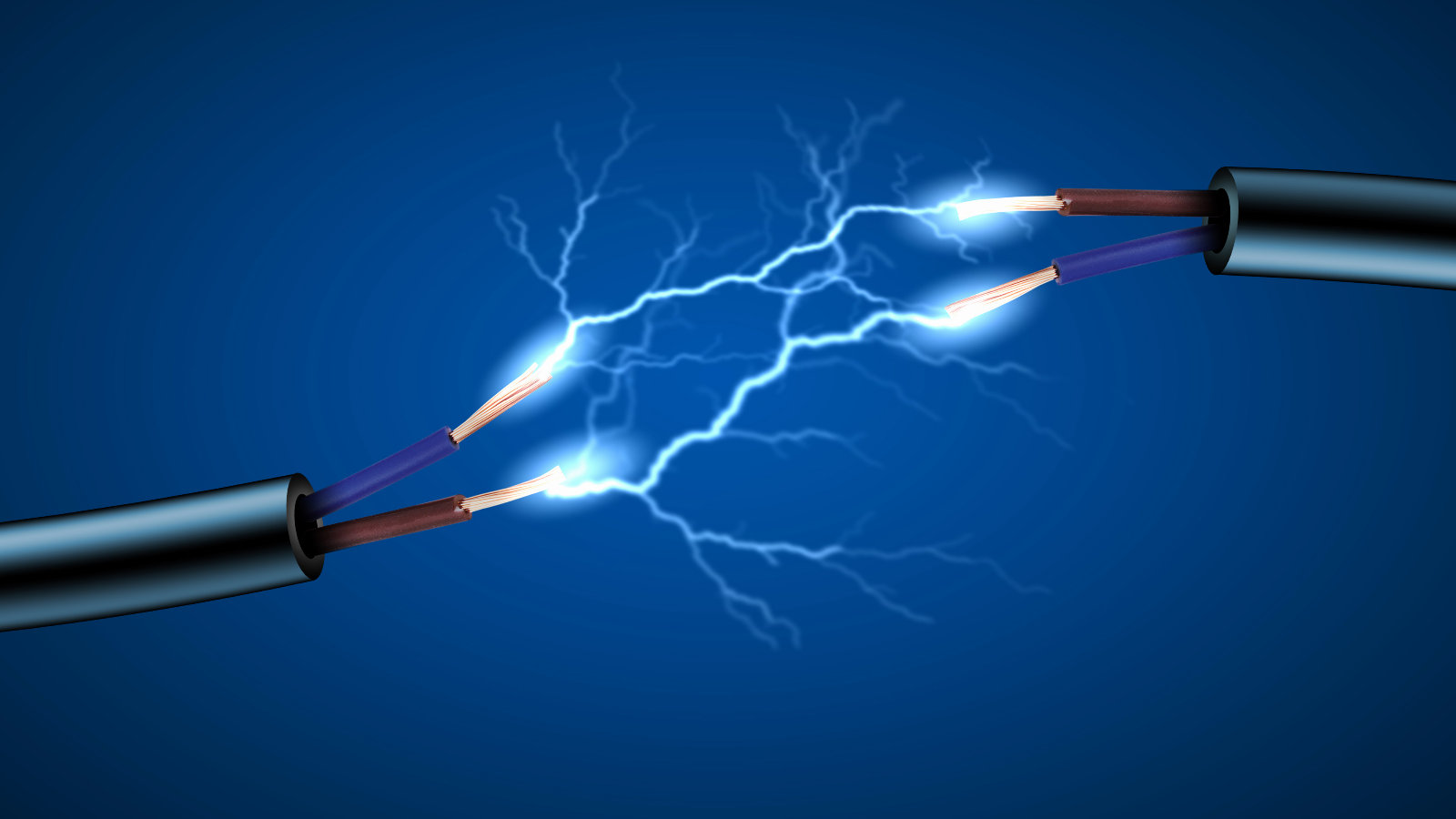

Bingo! Thanx, Marg! That answer was "no." We sent the email to the marina and moved back to our old slip after work on Monday. Just the comfort of the familiar? Maybe. But then we realized what we had seen in the new slip, the one where first Dan, then I, was concerned about exposure to the north wind. This photo shows the bumper on the piling at midships. See the abrasion? Granted that their boat was a different size and shape than ours so our results might not have been the same, but during at least one storm over the last couple of years, the former slipholders couldn’t quite keep the wind from pushing them onto the pilings.

|

| Abraded dock bumper: this should have told us that the problem of strong north wind was significant. |

(Originally published in the Capital-Gazette on May 22, 2013)